Privacy ≠ Freedom (but it should)

The data is in. Privacy is not correlated to Freedom. It is time to rethink how we write privacy laws.

In 1967, Alan Westin published Privacy and Freedom in response to growing concerns in the 1960s about computer databases and surveillance. Westin argued that encroachments on privacy were also encroachments on 'American liberty.' When he stated that "Privacy is the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others"[1], he argued that privacy (liberty) was not possible without individuals having both the autonomy to both make these claims and to have them respected.

In the 60s, there was a growing concern about technology encroaching on privacy. He argued, "The real need is to move from public awareness of the problem to a sensitive discussion of what can be done to protect privacy in an age when so many forces of science, technology, environment, and society press against it from all sides."[2]

The US Privacy Act (1974) was the first legislative response, followed by the OECD privacy guidelines (1980) and the Council of Europe Data Protection Convention in 1981. Data protection or privacy laws have become the norm in the 50 years since the US Privacy Act. However, the concerns expressed then are just as valid today, whether from a left view of Surveillance Capitalism or a business school description of an Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Despite the proliferation of privacy laws, privacy is as much under threat today as it was then.

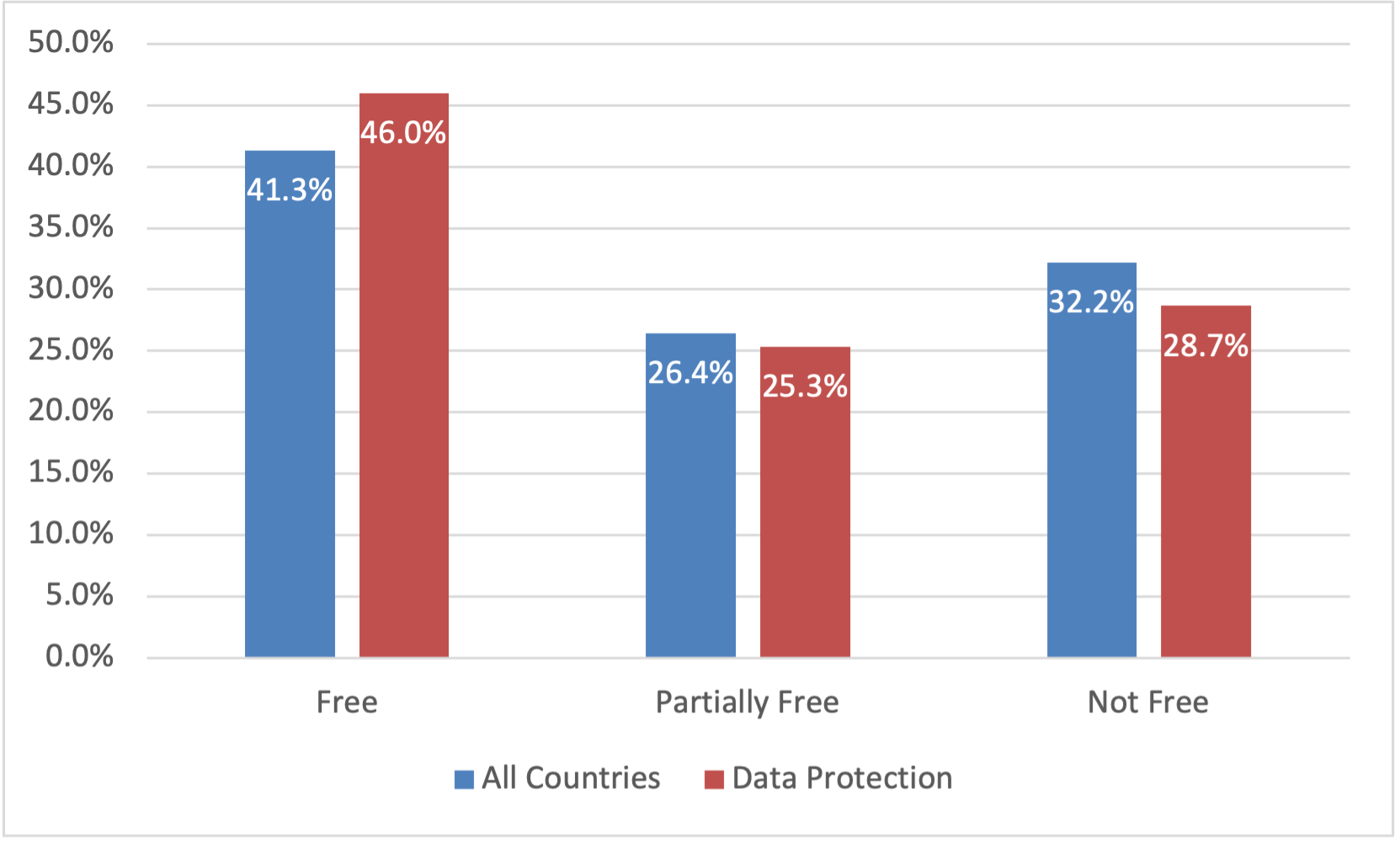

Returning to "Privacy and Freedom", does the failure of privacy mean a failure of freedom? Is the likelihood of a country being free, partially free, or not free uncorrelated with whether or not the government has data protection or privacy laws? There are more than 200 countries in the world, 150 of which have some form of privacy or data protection legislation[3]. Freedom House's Annual Freedom in the World report categorises countries as "Free", "Partially Free", or "Not Free" based on a set of 25 indicators[4]. When you compare the percentages of countries' freedom ratings, the impact of having privacy or data protection legislation on whether or not a country is free is minimal.

| Total Countries | 208 | 100 % | DP Countries | 150 | 100% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free | 86 | 41.3% | Free | 69 | 46.0% | |

| Partially Free | 55 | 26.4% | Partially Free | 38 | 25.3% | |

| Not Free | 67 | 32.2% | Not Free | 43 | 28.7% |

This suggests that privacy itself is not related to freedom (or liberty) OR that there is a problem with the way that privacy laws have been written or implemented. The proposition that privacy should be concomitant with individual freedom and that the ability of groups to organise seems almost axiomatically true. And recent writings suggest that, as currently architected, privacy laws can be helpful for authoritarian governments.[5]. This echoes critiques from privacy scholars such as Woodrow Hartzog[6] or Ignacio Cofone[7]. In a recent article, Daniel Solove says, "To adequately regulate government surveillance, it is essential to also regulate surveillance capitalism. Government surveillance and surveillance capitalism are two sides of the same coin. It is impossible to protect privacy from authoritarianism without addressing consumer privacy."[8]

Without trying to be hyperbolic, the current trajectory for privacy laws and regulations is leading down a path of digital alienation. It is time for privacy laws and practices to support digital autonomy.

Footnotes

- Westin, Alan F.. Privacy and Freedom (p. 5). ↩︎

- Westin, Alan F., Privacy and Freedom (pp. 1-2). ↩︎

- See UNCTAD Data Protection and Privacy Legislation Worldwide ↩︎

- See the Methodology Scoring Process at https://freedomhouse.org/reports/freedom-world/freedom-world-research-methodology ↩︎

- Jia, Mark (2024) "Authoritarian Privacy," University of Chicago Law Review: Vol. 91: Iss. 3, Article 2. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclrev/vol91/iss3/2 ↩︎

- Privacy's Blueprint: The Battle to Control the Design of New Technologies https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674976009 ↩︎

- The Privacy Fallacy: Harm and Power in the Information Economy https://www.privacyfallacy.com/ ↩︎

- Solove, Daniel J., Privacy in Authoritarian Times: Surveillance Capitalism and Government Surveillance (January 19, 2025). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5103271 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5103271 ↩︎